Interview by Mary Godin

As Direct Support Professional (DSP) Week 2025 draws near, Excentia Human Services CEO Chris Shaak reflects on the beginnings that shaped him. From his earliest nights on shift as a caregiver to overseeing a human services organization today, Shaak’s career traces a story of compassion and the kind of leadership rooted in lived experience.

Sitting down with us, he speaks candidly about trial-by-fire lessons, the weight of responsibility, and why servant leadership remains at the heart of everything he does.

Mary Godin: You started your career as a DSP in 1990. Can you discuss what originally inspired you to pursue a career as a direct support professional and what that role looked like back then?

Chris Shaak: Yeah, I mean, I think what inspired me was coming out of IUP (Indiana University of Pennsylvania) at the time with a criminology degree, and wanting to gain entry into any public human service job. I was married at the time, and we were expecting, and it was a job that was readily available.

Mary Godin: Can you share what a typical day looked like for you during that time?

Chris Shaak: I started out as what they called a caregiver—or direct care staff, as the title was back then. Today, it would be known as a direct support professional. My first role was on what we now call the overnight awake shift, working in a home with four men who each had varying levels of intellectual disability. Some needed a great deal of support, while others were fairly independent.

My shift began around three in the afternoon, right as the men were coming home. I’d help with daily chores, dinner, and activities—sometimes that meant shopping, other times just a walk around the IUP campus next door. Evenings were about creating normal routines—cooking, eating together, watching TV—before I went to bed around ten. Then, by 6:30 the next morning, I was up again, helping everyone get ready for the day, dressed, and fed before my shift ended at nine.

Back then, sleep hours weren’t compensated unless you were called awake—a practice that has since changed with the addition of overnight stipends. Even so, those early days became invaluable, teaching me responsibility and patience.

Mary Godin: What would you say was the most challenging aspect of that role for you?

Chris Shaak: The most challenging part was just how new it all was to me. I’ll never forget my very first shift. My supervisor that night was a veteran—she had been in the field a long time and really knew what she was doing. The first thing we did was take the guys to Kmart to pick up toiletries and supplies. One of the men I was supporting had severe cerebral palsy, an intellectual disability, and epilepsy. While we were waiting in line, he suddenly went into a full grand mal seizure. I had never seen anything like that in my life. His eyes rolled back, his body stiffened, and then—after the seizure—he was completely drained, almost faint.

To make matters harder, the medications he had to take for epilepsy required laxatives, so in the middle of this episode, he also relieved himself. There I was—brand new on the job, standing in a crowded line at Kmart—completely overwhelmed. My supervisor stayed calm, told me to grab towels, and together we got him to the van. Back at the house, which was a big old Victorian with steep steps, I literally had to fireman-carry him inside and up to the shower to make sure he was cleaned up and comfortable.

That experience was a true trial by fire. I had no training, no preparation; I was just thrown in. Today, things are so different. New staff receive thorough training before they ever step foot in a house. Back then, it was just, ‘You’re hired. Here’s the job. Go do it.’ And that just showed me just how much there was to learn.

Mary Godin: When you look back on that time, do you think there are any pivotal moments that you experienced when you were a DSP or caregiver that changed your perspective on leadership or business in general?

Chris Shaak: That moment gave me real perspective. I can’t remember my supervisor’s name now, but she was excellent, calm under pressure, patient, and fully aware that I was brand new and unsure of myself. She was never demeaning; instead, she guided me, let me make mistakes, and taught me through them. I worked in that role for about a year, and that period was truly pivotal for me. It shaped my understanding of what it means to serve others—an idea I’ve carried forward and continue to believe in strongly today. I’m a huge fan of servant leadership.

Mary Godin: Now, can you walk through your experience after that with your career and how it evolved?

Chris Shaak: After my first role, my wife and I moved back to my home county, Lebanon, where I secured a job at a place called Sherwood Hall, which has since closed. It was a campus-based facility that combined group homes for adults with programs for court-involved youth identified as having intellectual disabilities. Some were referred by Children and Youth Services, others through Lancaster County’s Special Offenders Program. Looking back, it was a model that would never be allowed today, but at the time it was considered standard practice.

At Sherwood Hall, I first worked full-time in the day treatment program. Heading into summer, they asked me to design programming for the kids who would normally be in school. The assignment was simple: keep them off campus during the day. They gave me a van, an assistant—who happened to be the maintenance guy, and who’s still a friend to this day—and about 20 teenagers with varying levels of ability. We got creative, asking local bait-and-tackle shops for donated rods and gear, and fishing became our big activity. We took day trips to places like Gettysburg, drove around the tri-county area, and kept the days full. It wasn’t ideal, but we made the best of it.

After about a year, I transitioned into a new role as activities coordinator at Halcyon Activity Center in Lebanon, which is still around today. It functioned as a drop-in center, serving a mix of people, many veterans from the nearby VA, as well as individuals with intellectual disabilities. Some came daily to drink coffee, talk, and socialize, while others participated in planned outings and excursions. The intellectual disabilities group used the center as their hub, and we organized weekly activities to get them out in the community.

That job brought some unforgettable experiences. One year, we organized a group trip to Nashville with 30 individuals, just four staff, one van, and an adventure. We stopped in Gatlinburg, visited Dollywood, took helicopter rides over the Smoky Mountains, and ended up at the Grand Ole Opry. Walking down the streets of Nashville with all 30 wearing cowboy hats is an image I’ll never forget. On the mental health side, we also led trips to Virginia Beach, where the focus was more on daily safety and structure. Both groups taught me different lessons about care, responsibility, and flexibility.

Halcyon was also where I started to gain management experience. My executive director, John, was a mentor who introduced me to data and outcome tracking, just as computers and Excel were becoming common. He showed me how to link funding to outcomes, how to measure impact, and how to use data to tell the story of the work we were doing. That was a new and important lesson for me.

Those experiences laid the groundwork for my next step: juvenile probation at the county, where I stayed for much of the 1990s. The systems-level understanding I had gained from Sherwood Hall and Halcyon proved invaluable. During that time, I also completed a master’s in Administration of Justice through Shippensburg University—a program offered to juvenile probation officers who committed to serving at the county level for two additional years.

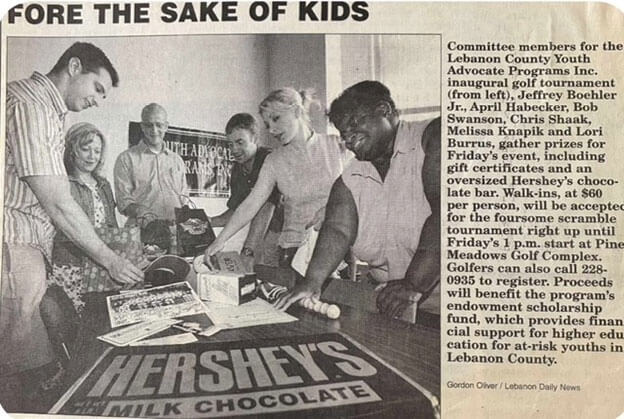

After probation, I joined Youth Advocate Programs in Lebanon, my first role in the private sector as a program director. That position came full circle to the work we do now at Excentia—it included therapeutic staff support, behavioral consultation, and contracts with the county for juvenile justice and child welfare programs. Everything was community-based—alternatives to detention, hospitalization, or placement.

All of those roles—spanning direct care, program management, probation, and advocacy—ultimately prepared me for my work at Excentia. The lessons from those early years continue to shape the way I lead today.

Mary Godin: We appreciate you walking us through that. What leadership lessons did you take from working closely with clients, teams, or systems?

Chris Shaak: I think the leadership lessons I’ve learned, particularly in the realm of human services, are grounded in a simple principle: support and lead your staff the same way you support the people you serve. Our work is about providing care with empathy, trust, and compassion, and I believe that same relationship-based approach should guide how we treat employees. When leaders build genuine relationships with their teams—whether it’s frontline staff, senior leadership, or an executive team—it creates trust and collaboration. That approach, I’ve found, is far more effective than an authoritarian style, and it remains true today.

Mary Godin: What do you think organizations today could learn from DSP work?

Chris Shaak: I think businesses in general could learn a lot from the work ethic of direct support professionals. The flexibility and resilience required in this field are enormous. At any given time, shifts can change, staff may be asked to cover for someone who didn’t show up, or they may be placed in a completely new environment. Beyond the challenges of supporting individuals directly, there’s also the constant logistical juggling that most people don’t see. Their example of flexibility, dedication, and compassion is something any business could learn from.

Mary Godin: If you could go back, what advice would you give your younger self starting out as a DSP?

Chris Shaak: Looking back on my early days as a DSP, one thing that stands out is how different the approach to behaviorally challenging situations was at the time. In the 1990s, the instinct was often to be hands-on first and try to de-escalate later. It was almost expected—by staff and even, in some ways, by the individuals themselves. With perspective, I now see how flawed that was, almost like the idea that violence begets violence.

Today, we know simple de-escalation techniques make all the difference, but at the time, I couldn’t have given myself that advice because I didn’t know any better. That was simply the way things were done. I was just following the norms of the day, even when those norms didn’t make sense.

At Sherwood Hall, many of the individuals had histories of institutionalization. Some had spent decades in hospitals, where if you got out of line, you were restrained. It was horrible, but that mindset was carried over even after people moved into the community. I remember one individual, Larry, who liked to smoke a pipe. One day, I was outside with him, trying to light it, and the weather made it difficult. Suddenly, he exploded—ripped a piece of spouting off the building and came after me. I found myself ducking, tackling, and just trying to keep everyone safe as chaos unfolded.

There were other constant challenges, too. Many of the kids were runners, always taking off, and we’d be chasing them across fields and roads. It was exhausting, unpredictable, and at times overwhelming. But that was the reality then. Today, with programs like CPI (Crisis Prevention Intervention) and Welle Training, we emphasize empathy, prevention, and de-escalation—and the difference is night and day. If I could give my younger self advice, it would be to approach those moments with calm first, not physicality. That shift has changed the field for the better, and it’s one of the clearest examples of how far we’ve come.

Mary Godin: So, what advice would you give to DSPs in today’s world?

Chris Shaak: My biggest advice to DSPs today is this: never stop learning. Take advantage of every training and educational opportunity offered to you. That’s why we put so much emphasis on professional development—whether through our training department, tuition assistance, or even exploring programs that could eventually support bachelor’s and master’s degrees. The more knowledge and preparation you have, the stronger you’ll be in this work.

Equally important is taking care of yourself. Self-care is one of the lessons I hear most often from graduates of our training programs with Millersville University. Learning how to set boundaries, even saying no to a shift when necessary, is crucial. If you’re doing your job the right way, you won’t be punished for taking care of yourself. Burnout is real, and avoiding it is essential to staying in the field long-term.

This work isn’t for everyone—some people try it and move on. But for those who feel called to human services, being a DSP is one of the very best places to start. It’s hard work, but it can be incredibly rewarding, and it lays the foundation for a meaningful career.

Mary Godin: Yeah, I would agree with that completely. So, one final question for you. How do you ensure that the values and lessons you learned from your DSP experience and even just your career are reflected in our company culture today?

Chris Shaak: How do I ensure that my values are reflected in leadership? Honestly, I think it comes down to things like this—sharing my story. Whenever I speak with staff, I often share the same stories from my time as a DSP. That connection matters because it shows people I’ve been where they are. I never want to be in an ivory tower.

I’ve also had mentors who shaped me along the way—some excellent, and some not so good. And the truth is, you learn from both.

What I try to carry forward is the same lesson I learned from my very first supervisor in the group home. She was calm, patient, and understanding of the fact that I was brand new and overwhelmed. Instead of micromanaging, she gave me room to learn. That approach, steady, reassuring, relationship-based, was pivotal for me then, and it continues to shape how I lead now.

Mary Godin: Anything else you’d like to say for DSP Week 2025?

Chris Shaak: I know I may sound like a broken record, but I’ll say it again, I truly believe we have some of the best DSPs in the field. I hear stories all the time about the extraordinary work they do. People like Keith Righter, who has dedicated more than 40 years to this role, come to mind immediately. His commitment says a lot, not only about his passion for the individuals he supports, but also about the kind of company Excentia is, one where someone would choose to spend their career and retire.

It’s true, DSPs are often overlooked in the broader workforce. You’ll hear words like dedication, endurance, and compassion in proclamations for DSP Week—even from the governor—but the reality is that this field doesn’t get the recognition it deserves. That makes it all the more important to celebrate and uplift those who choose this calling. They deserve to be commended.